Blood Martyrs of the National Socialist Movement

The Year 1929

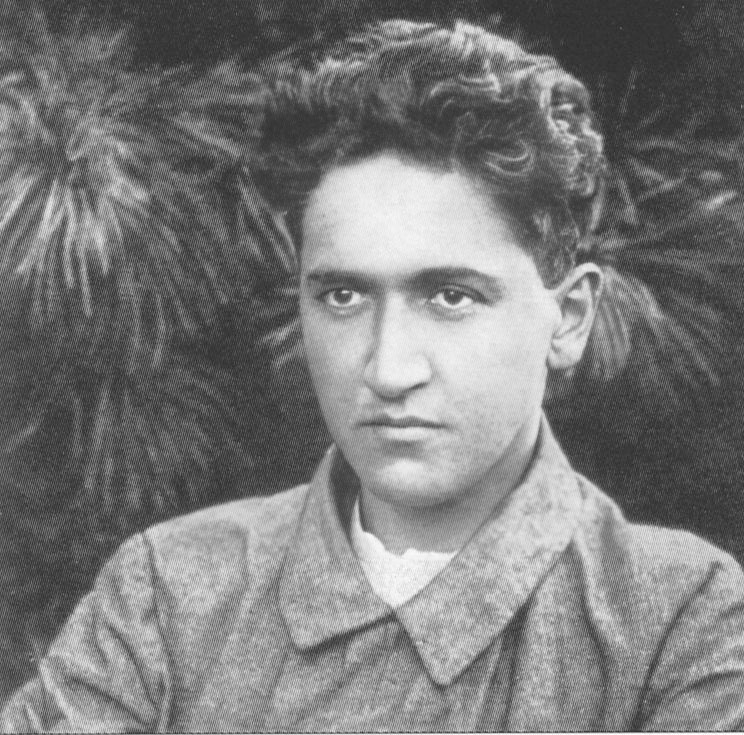

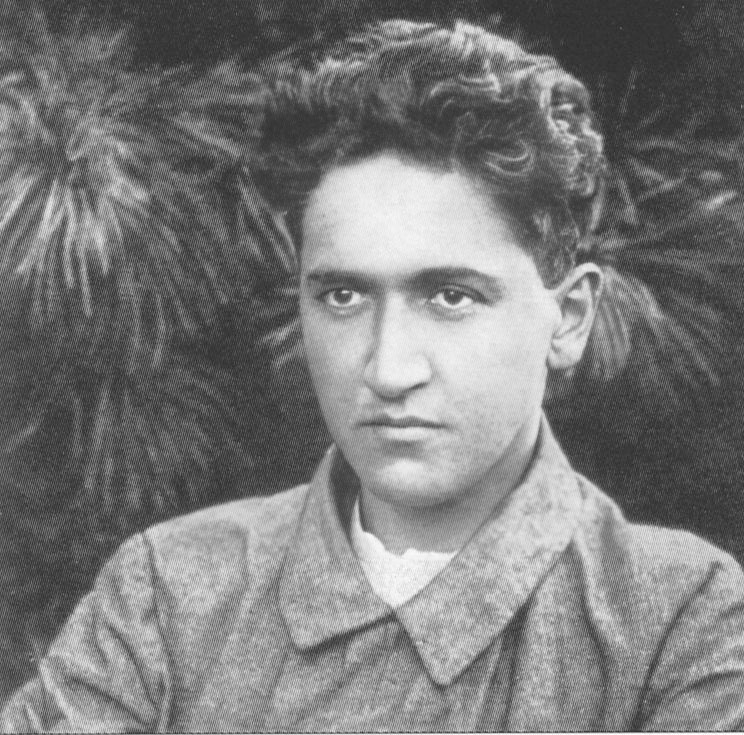

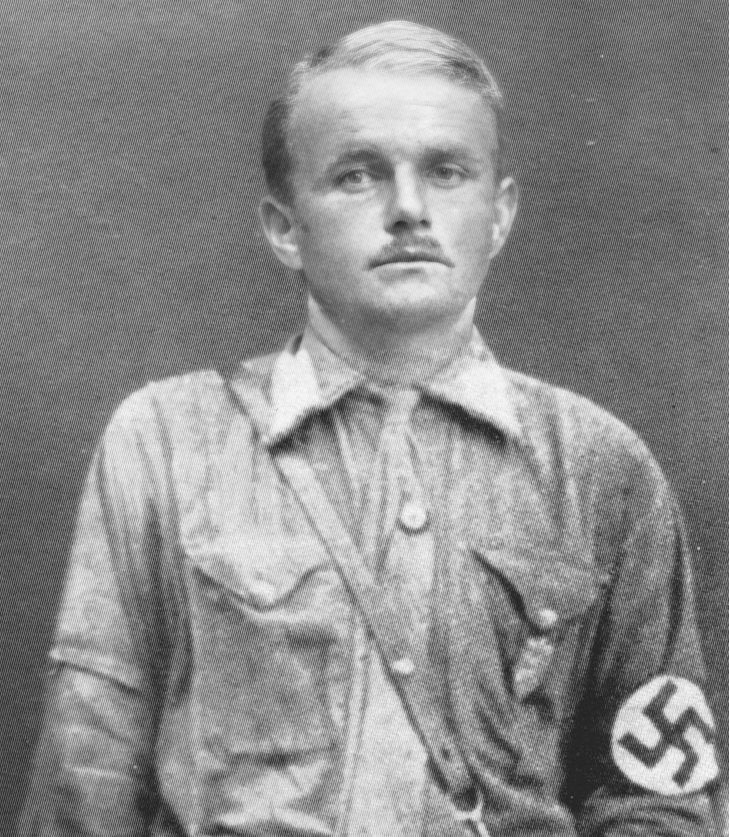

Heinrich Limbach

(* 19 December 1898 in Zweibrücken, † 8 February 1929)

Heinrich Limbach was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr to the National Socialist movement.

Life

Heinrich Limbach was born in Zweibrücken, Palatinate, and moved with his mother and siblings to Leipzig in 1914. In Podelwitz near Leipzig, an NSDAP flag-raising ceremony took place as early as 13 September 1923, in which the local SA took part. A massive communist attack broke up the event. Heinrich Limbach was driven by the attackers into a marshy area above the railway embankment. His pursuers caught up with the twenty-four-year-old locksmith and pulled him to the ground. Robbed of his valuables and party book, Heinrich Limbach was severely maltreated. The SA man manages to drag himself to the vicinity of the cemetery, where he is found and taken to the St. Georg hospital. Head wounds have to be treated as well as a multiple fracture of the hand. The hard blows of the attackers have injured the kidneys, which in the course of time leads to severe suffering.

For years Heinrich Limbach remained active in the NSDAP and the SA, and heard Adolf Hitler speak in autumn 1928. From Christmas 1928 onwards, the sick man's condition deteriorated more and more. Limbach died on 8 February 1929 after suffering for almost six years. His comrades of the Leipzig SA bury him on 11 February 1929.

Death

On the way to a flag consecration in autumn 1923, the National Socialist Heinrich Limbach, a young locksmith from Leipzig, said to a comrade: „I want to die like Schlageter!“ On the same day he was attacked and injured by communists. He wasted away from his wounds for more than five years until he died of their consequences on 8 February 1929.

Commemoration

On 8 November 1938, a solemn procession took place in Leipzig, during which the coffins of the seven Leipzig Blood martyres Walter Blümel, Alfred Kindler, Erich Kunze, Heinrich Limbach, Alfred Manietta, Erich Sallie and Rudolf Schröter were first brought from the North Cemetery to the Markt, where the dead were called „to the last roll call“. Instead of them, the formation of honour responded with „Here!“ when each name was called. The coffins were then transferred to the grove of honour specially created for them at Leipzig's South Cemetery.

In 1936, a green space in the Leipzig district of Gohlis was named „Limbachplatz“ after the dead man.

Hermann Schmidt

(*29 October 1908 in St. Annen, † 7 March 1929 in Wöhrden)

Hermann Schmidt was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement who lost his life in the Bloody Night of Wöhrden. Adolf Hitler personally attended the farmer's funeral.

In Kiel, a street was named after Hermann Schmidt.

Otto Streibel

(6 November 1894 in Röst, Holstein, † 7 March 1929 in Wöhrden, Holstein)

Otto Streibel was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement who lost his life in the Bloody Night of Wöhrden. Adolf Hitler personally attended the carpenter's funeral.

The road from Albersdorf to Röst was renamed from Mühlenstraße to Otto-Streibel-Straße. In Kiel, a street was also named after Otto Streibel.

Katharina Grünewald

(* 29 April 1904, † 2 August 1929 in Nuremberg)

Katharina Grünewald was an opponent of the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement.

Katharina Grünewald was one of three female Blood martyres of the Nazi movement. She was born Katharina Fülbert in Worms on the Rhine and spent her youth in Frankfurt am Main, the residence of her parents.

After leaving school, Katharina Fülbert went to Lampertheim in Hesse and managed her grandfather's household there.

In 1924, the young woman married the merchant Georg-Ludwig Grünewald and ran a grocery shop with him.

Through her husband, who led the local NSDAP group in Lampertheim in 1927, Katharina Grünewald came into contact with politics and belonged to an early group of the NS Frauenschaft.

The research on the circumstances of the death does not provide a clear picture of the events. The mother of a young son attended the 1929 Reich Party Congress in Nuremberg with her brother.

On the evening of 2 August, after the fireworks, the two walked towards their accommodation. At Museumsberg, between Lorenzplatz and Museumsbrücke, a car belonging to the Supreme SA leadership drove past. Several members of the Reichsbanner tried to stop the vehicle at the corner of Karolinenstraße directly in front of St. Lorenzkirche. When they failed to do so, one of the persons fired several times at the car. A stray bullet fatally hit the twenty-five-year-old near the heart. The shooter was arrested by the police, according to the „Völkischer Beobachter“.

This is the most detailed and unambiguous account of the bloody deed; however, it is unequivocally denied by the police in the „Fränkischer Kurier“ of 15 August 1929, without, however, giving further details. There is only talk of crowds and scuffles between SA and Reichsbanner members, which finally culminated in the death of the young woman.

Shortly afterwards, members of the NSDAP were sought as witnesses in newspaper advertisements. They were said to have had a heated exchange of words with the Reichsbanner men near the scene of the crime.

Memorial for Katharina Grünewald

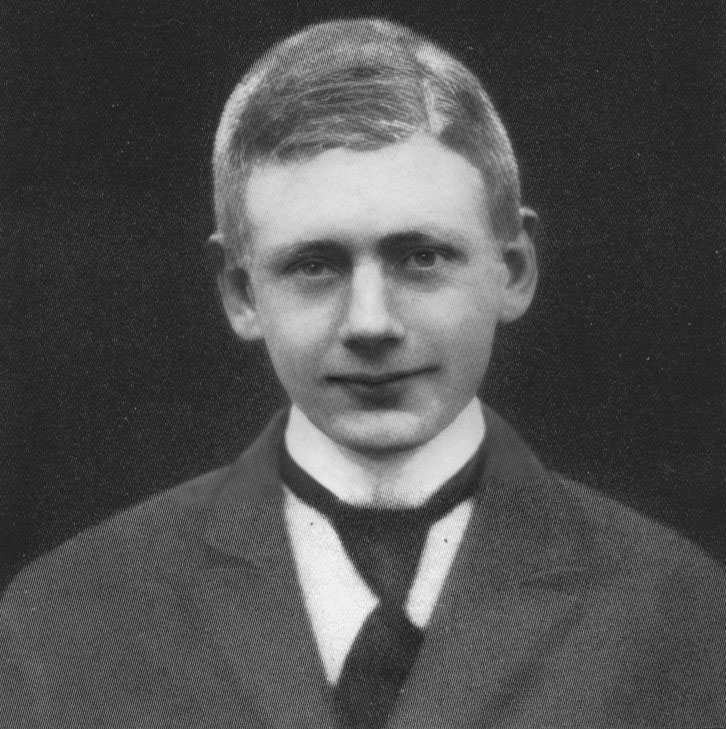

Erich Jost

(* 4 March 1909, † 5 August 1929 in Nuremberg)

Erich Jost was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr to the National Socialist movement.

In the Kulturverein garden in Nuremberg, a group of SA men were still sitting together when the main part of the party conference was already over. Among them was Erich Jost from Lorsch near Bensheim in Hesse, who was talking to his comrades about Hitler's speech. The SA man had already been a member of the party and the Sturmabteilung for several years. Now he had heard his Führer speak for the first time.

Erich Jost was born in Gießen as the son of Adolf Jost, a court assessor. Between 1914 and 1918, the boy attended primary schools in Waldreichenbach. He then spent several years at the „Türck“ boarding school in Seeheim, Hesse.

After school, Erich Jost took up a merchant's profession. On the summer night that was to be his last, the SA man went out of the garden pub once more onto the street, perhaps to see one of the vehicles in which Hitler and the party leadership were going to their quarters after the final rally. Shortly afterwards, his SA comrades received a report that the twenty-year-old had been seriously wounded by a knife attack by members of the Reichsbanner.

Contemporary press sources do not describe this incident either. It is only written about the deceased National Socialist Jost: „[...] who received a 16 centimetre long stab wound in the back near the Kulturverein that night [...]“. Hitler visited the injured SA man at his bedside in the Theresien Hospital in Nuremberg. An operation could not save the SA man. Erich Jost died on 5 August 1929 as a result of a „ruptured bladder“. Hitler was personally present at the funeral in Lorsch. A contemporary source reports on the funeral ceremonies with the pathos common in all political groups of the time:

„[...] There is a hustle and bustle in the little town. Lorry after lorry arrives on the market square. From Weinheim, from Heidelberg, from Darmstadt, Eberstadt, Worms and Mannheim, from the Palatinate and from Baden, from Rheinhessen and from Frankfurt Brown is the colour of the streets. There is a hustle and bustle, the whole of Lorsch is on its feet, a crowd that cannot be overlooked. Then it roars from the streets further away, stronger and stronger to the thousand-voiced cry of salvation. - A grey car stops on the market square - Adolf Hitler has come to give his last salute to his SA comrade. The cemetery, the surrounding fields black with people. A murmur goes through the masses, Adolf Hitler walks through the rows, stands in front of the open tomb. He speaks: What crime has he committed who lies down there? Because he loved his fatherland, he had to die. Can we take responsibility for the murdered man in our ranks? Yes, we take responsibility for the death of our comrade, because each of us is always ready to make the same sacrifice. The same sacrifice was made on the way to the liberation of Germany. It is up to us to ensure that these sacrifices are not made in vain, like the two million heroic sacrifices of the World War, which were made in vain because patriotic scoundrels and criminals robbed the heroes of the meaning of their sacrifice. We have the unshakeable will to win. One day freedom will break out over this people, then the resting place of this dead man will have long since become a place of pilgrimage. He will remain unforgotten. Now he lies disembodied, but his soul will find no rest until the day when Germany is free again. Just as he said he would die once more for our freedom if he could, so we are all ready to take the same path. The dead man sleeps - Germany awake!'

The flags lower over the tomb [...]“

In 1933, the SA storm 11/221, later 9/186, was named after Erich Jost.

Erich Jost was honoured at the Reich Party Congress in 1929. Later, the Reich Labour Service camp in Lampertheim was named „Erich Jost“.

Heinrich Bauschen

(* 18 March 1893, † 19 October 1929 in Duisburg)

Heinrich Bauschen was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement.

Heinrich Bauschen joined the NSDAP as early as 1922. He took part in the march on the Feldherrnhalle. On 18 October 1929, a number of boys on their way home from a lecture evening of the National Youth were attacked and maltreated by communists in Duisburg's Gutenbergstrasse. In response to their cries for help, Heinrich Bauschen, a railway worker from Duisburg, rushed over with several comrades to help the oppressed. During the ensuing fight, Heinrich Bauschen, a war-disabled man, was stabbed in the thigh, severing the artery. That same night he gave up his life, with which he had protected the German youth.

The „Kameradschaft Duisburg“ bears his honorary name „Kameradschaft Heinrich Bauschen“.

Karl Rummer

(*6 June 1907, † 20 October 1929 in Schwarzenbach am Wald)

Karl Rummer was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement.

On 16 June 1929, Adolf Hitler spoke in Schwarzenbach am Wald under the sign of the Döbra “Swearing Of The Oath” Ceremony. His words also shook up someone who had previously belonged to the mass of SPD supporters, Karl Rummer from Schwarzenbach. He unreservedly declared his allegiance to the NSDAP and joined the SA.

On 5 October 1929, he went with SA comrades and party comrades to a Social Democratic meeting where a Social Democratic member of the Landtag spoke about the adoption of the Young Plan. The counter-speaker was a National Socialist. This was the signal for the Social Democrats to throw beer glasses at him and to beat the National Socialists present with clubs. Karl Rummer was injured. When he was on his way home, he was attacked again by Reichsbanner people and beaten up so badly that he collapsed, covered in blood and unconscious. His wounds caused his death in the hospital in Hof on 20 October 1929.

Gerhard Weber

(* 10. 9. 1907 - † 4. 11. 1929)

Dirstrict Berlin, SA Group Berlin-Brandenburg

Weber is mentioned in all NSDAP lists as a Blood martyr of the movement. Descriptions of the circumstances of his death, however, are rare. The background may lie in the fact that even in the SA there were doubts about the political background of the deed.

The NSDAP local group Berlin-Wilmersdorf held a meeting on L6. October 1929 a meeting against the adoption of the Young Plan. In the venue of the event, the restaurant „Forsthaus“ at Wamemünder Straße 8, there was a serious hall fight with communists.

During the journey to the meeting, the SA squad leader of the Steglitz SA Storm 3, Gerhard Weber, was wounded by a stone thrown in Lentze-Allee in the Berlin district of Dahlem. The twenty-two-year-old driver died two weeks later as a result of the injury.

Contemporary sources close to the National Socialists also state that it was probably a communist attack. This assumption was obvious to the dead man's comrades. Weber had driven through the capital in SA uniform. Throwing stones at „fascists“ was nothing unusual. Doubts about a political murder nevertheless seemed to remain.

Friedrich Meier

(*3. März 1906, † 8. Dezember 1929)

District Kurmark, SA Group Berlin-Brandenburg

Friedrich Meier was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement.

The journeyman blacksmith from Württemberg had to give up his profession because his body was too weak for it. Friedrich Meier wandered through all the German districts until he settled in Falkensee near Berlin as a farm labourer. He joined the NSDAP and led the local group in Falkensee. He devoted all his efforts to the party and worked tirelessly to strengthen the movement. On a propaganda trip to Nauen he was attacked by communists and seriously injured. After a long stay in hospital, he resumed his party service with all his characteristic tenacity. He moved to Kyritz, where he found work. When he returned from a meeting on the night of 16-17 November 1929, he was so badly injured in a street fight by SPD people, who threw stones at him and beat him with steel rods, that he succumbed to his wounds on 8 December 1929 after unspeakable agony. He took his leave with the words:

„I know that I must die and I also know what I am dying for. Give my regards to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels. Be faithful and do your duty.“

Walter Fischer

(*20 March 1910, † 14 December 1929 in Berlin)

Walter Fischer was a resistance fighter against the Weimar Republic and a Blood martyr of the National Socialist movement.

Quote from a comrade of Walter Fischer:

„Through nocturnal street echoes the step of the boy. That’s what got us up again: Thunder again, the doctor has given it to the chaos again, just now in the crowded Viktoriagarten. Goebbels, if he doesn’t make it here in Berlin, nobody will. It was pathetic what the commune’s Rau said in the discussion, we laughed at him. But the guy was rushing again - if that doesn’t make the air thick again! But we are still here, thank God, he laughs to himself.

Then he becomes serious, quietly sad.

Actually, I don’t belong to it any more. Because of father. He’s a chauffeur for the police colonel Heimannsberg, for that big shot. And he fears for his position if the boy is in the SA. He fled and raved and threatened to expel the lout if he didn’t leave the party.

He, the nineteen-year-old, has had to obey. Outwardly, yes. But inwardly? No way, you have to be loyal to Adolf Hitler. He secretly goes to the meetings, puts on his brown shirt, just like today. (...) Defiance shines in his eyes. And yet I belong to it.

He turns into Brandenburgische Strasse. There - shots ring out - that’s the Sturmlokal over there. SA comrades are already coming at the double. „It’s you, Walter Fischer? Communist raid! We’re following, come with us.“ And he runs along to Sigmaringer Strasse, where the communist bar is. The riffraff shoots out of the bar.

Walter Fischer leaps forward, he can join in the fight, beats his heart joyfully, there in his left breast. Something beats against it from outside. He sinks down. The bullet tore the artery. He was killed instantly.“

Joseph Goebbels attended the funeral service, Hermann Göring gave the eulogy.

A street was named in his honour in Berlin-Wilmersdorf.

Hermann Göring speaks at the grave of his dead comrade Walter Fischer,

Berlin, at his funeral on 13 December 1929