The Blood Martyrs of the National Socialist Movement

Felix Allfarth (1901-1923)

He was born in Leipzig on 5 July 1901. He completed his school education in 1917 with a travel certificate. After his commercial apprenticeship at the Siemens Schuckert Works, he came to Munich on 1 July 1923. There, his national attitude led him, enthusiastic for his fatherland, to join Adolf Hitler. with the Deutschlandlied on his lips, he dedicated his life to the fatherland and Adolf Hitler.

Andreas Bauriedl (1879-1923)

Born on 4 May 1879 in Asaffenburg, Bauriedl joined the Infanterie-Leibregiment in 1899. There he was discharged as a non-commissioned officer in 1901. At the beginning of the war, he went into the field with the Landwehr regiment in the very first days. In 1916, after the disbandment of his regiment in Vilsbiburg, he returned home as a deputy officer. During the four years of war he was able to earn the Medal of Merit with blue ribbon and the Iron Cross Second Class. Back home, he immediately volunteered for the local army and joined the NSDAP in 1923. Here he became platoon leader of the 6th company. He fell at the Feldherrnhalle as a bearer of the blood flag.

Theodor Casella (1908-1923)

Casella’s father was a professional soldier and fell as a major in October 1914. So, Theodor, born on 8 August 1900, came to the cadet corps for his education. In 1917, he then joined the field artillery regiment No. 7 in Munich as an ensign. He was immediately sent to the front, where he fought before Verdun and Reims. He is then promoted to lieutenant and becomes holder of the Iron Cross and Mlitäruerdienstkreuz with swords. In October 1918 he is seriously wounded and retires from the army in 1919. He enrols as a student at the University of Munich, but earns his money as a bank clerk on the side. When the Freikorps Epp is formed, he participates in the liberation of Munich, then goes with them to the Ruhr and Upper Silesia. He then becomes a member and company commander of the „Reichskriegsflagge“. On 9 November 1923, Casella was shot in the back at the military district command when he tried to pick up his seriously wounded comrade Martin Faust.

Kurt Neubauer (1899-1923)

Kurt Neubauer was born in Hopfengarten (W.P.) on 27 March 1899. At the age of sixteen he secretly left his parents’ home and volunteered in Graudenz. In the field he earned the E.K. II. After the end of the war he joined the Rossbach troop, marched with them, fought in the Baltic States, in Upper Silesia and in Westphalia. On 13 July 1920, he joined the 27th Jäger Battalion of the Reichswehr. Soon afterwards, however, he became a servant of Ludendorff. Indicative of his political attitude was a letter he wrote to his ‘mother on her birthday. „You will celebrate your next birthday in a new Germany. Adolf Hitler will lead us. Should he not succeed, we are prepared to fight on even if it takes another ten years. The people do not yet want to believe in Adolf Hitler, but they will have to believe in him one day!“ - His words became truth. He himself never lived to see it.

Klaus von Pape (1904-1923)

Klaus von Pape was born in Oschatz i.Sa. on 16 August 1904. In Munich he joined the „Bund Oberland“ in 1922 and led it in Herrsching, Seefeld and Oberalting. On 8 November, he proudly and happily drove to Munich with some comrades. There the bullets hit him, him who was allowed to carry the flag of the „Bund Oberland“ in front of the Führer. When he collapsed, the flag cloth covered him. His last words were: „Is Hitler alive, is Ludendorff alive? Then I will gladly die for my Fatherland!“ Despite immediate surgery and the transfer of his mother’s blood, his young life could no longer be saved. With a salute to his Führer Adolf Hitler, he died in his mother’s arms.

Theodor von der Pfordten (1873-1923)

Born on 14 August 1873, the councillor at the Supreme Regional Court in Munich was one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Adolf Hitler’s ideas. During the World War he was an officer at the front, where he was seriously wounded and unfit for frontline service. In word and deed he fought for the resurgence of our fatherland. His publications and lectures in the Euckenbund were significant. The administration of justice and the development of the law, not only in Bavaria but throughout the Reich, lost a champion in him. He died on 9 November 1923.

Wilhelm Ehrlich (1894-1923)

Ehrlich was born in Glowno (district Posen) on 19 August 1894. In August 1914, at the age of twenty, he joined the Landwehr-Inf.-Rgt. 10 in Breslau as a war volunteer. In December 1914 he went into the field and fought in the first heavy battles in Russia and in the Carpathians. In 1917 he was sent to the Western Front, where he remained until the end of the war. He was wounded and buried once. It was to his ‘courage and persevering bravery that he owed his rapid promotion. He was awarded the Iron Cress I and II class. After the war, he continued to work for the uplift of our fatherland and was in the border guard in the East in 1919, with Count Helldorf in Mecklenburg (Güstrow) in 1920, in the Kapp putsch and in the defensive struggle in the Rhineland (Cologne-Godesberg line) from 1922 to 1923. When arrested, he escaped from the French again and fled to Munich, where he immediately made himself available to the movement. He was also one of the 16th Blood martyrs who fell on 9 November 1923.

Martin Faust (1901-1923)

In February 1918, at the age of seventeen (born on 27 January 1901 in Hemau), he voluntarily enlisted in the navy and received his training on SMS. „Freya.“ Then he is transferred to SMS. „Großer Kurfürst“ and after the end of the war he was assigned to the delivery of the German fleet at Scapa Flow. In 1919 he returns and attends the commercial college. He then works in various banks, finally in Munich. In 1920 he joins the „Reichsflagge“, and in 1923 transfers to the „Reichskriegsflagge“, where he becomes a platoon leader.

He was also one of the 16th Blood martyrs who fell on 9 November 1923.

Anton Hechenberger (1902-1923)

Born on 28 September 1902, Hechenberger already joined the Schutz- und Trutzbund in his youth; for him, the most beautiful experience was when this union was once allowed to attend a meeting of Adolf Hitler. It was not until 24 November 1922 that he joined the NSDAP and the 6th Company. Before that he was in the Reichswehr from 1 January 1921 to July 1922, but left again to devote himself to his profession. On 9 November, his younger brother Heinrich, who later died in a motorbike accident, marched at his side. Anton himself died on 9 November 1923.

Johann Rickmers (1881-1923)

The son of a Bremen shipping company owner, he was born on 7 May 1881. During the World War, he spent four years in the Totenkopf Hussars. After the end of the war, the retired cavalry captain moved to Bavaria and joined the „Bund Oberland“, which he soon headed as leader. In the foothills of the Alps, where he had his country house in Oberalting, he established a strong base for the NSDAP and founded many local groups himself.

He was one of the 16 people killed on 9 November 1923.

Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter (1884-1923)

Child of a senior teacher’s family in Riga, where he was born on 9 January 1884 as a Reich German. He then studied chemistry and took his exams in Munich. At the outbreak of war, he volunteered and went to the Western Front with the 7th Chevauleger Regiment. In between, he was also used in the diplomatic service and was active in Turkey. He rendered special services in the liberation of Livonia and Estonia. Even after the collapse, he held out faithfully and, as a representative of the German Reich in Riga, cared for the German Balts with selfless devotion. He was arrested and narrowly escaped execution by the communists.

He fled to Munich, where he published Aufbau, a popular enlightenment series on the harm of communism.

Lorenz Ritter von Stransky (1899-1923)

Ritter von Stransky-Stranka und Greissenfels came from an ancient noble family whose coat of arms included the saying: „Thus indeed one sees what bravery has acquired!“ Stransky, having reached the prescribed age, had gone into the field with the Luitpold gunners and fought for the last two and a half years on the Flanders Front as a first lieutenant. After the war he was first with the Freikorps Epp and fought for the liberation of Munich. Then he joined the party and did a lot of publicity work. He founded local NSDAP groups in Württemberg and the Black Forest. After being active first in the Schul- und Trutzbund, he joined the SA. and fell on 9 November as a platoon leader with the 1st division of the 6th company.

Oskar Körner (1875-1923)

The merchant Oskar Körner was born on 4 January 1875 in Oberpeilau. He served his military service with the 15th Infantry Rgt. in Bielefeld. On 2 August 1914, he went to the Western Front, where he earned the Cross of Merit with Swords. After the end of the war, he joined the Einwohnerwehr and then the Völkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund. On 5 February 1920 he joined the NSDAP and did a lot of small work. Protecting meetings, putting up posters, partly pasting them over, tearing them away, painting swastikas wherever possible was something he did every day.

Adolf Hitler spent a lot of time with Körner; the Führer especially spent Christmas with the Körner family. Körner also signed the first party donation slips. He also earned great merit by founding the local groups in Koburg, Augsburg, Landshut, etc. Later he became second chairman of the party. On 9 November he saw the procession marching on Marienplatz, and when he came home from sweeping, he fell in line. When the first shots were fired and the Führer’s companion, Graf, collapsed, Körner stood in front of Adolf Hitler, but sank down, hit by terrible shots to the head and stomach.

Karl Kuhn (1897-1923)

Karl Kuhn was born in Heilbronn a.N. on 25 July 1897. At the outbreak of war, he was in London and smuggled himself into Germany with the help of a coal ship. He was buried on the Western Front in 1917, received a nervous shock and lost his speech completely. From this time on, he then became a waiter in Munich. Before that he was head waiter in the Heilbronn „Ratskeller“. He was also the first NSDAP member in this city.

On 9 November 1923, he took part in the march to the Feldherrenhalle in Munich. He was shot in the head and thus became one of the 16 Blood martyrs of 9 November!

This is denied today in Heilbronn. It is said today that he was a „passer-by“ who was accidentally hit....

Karl Laforce (1904-1923)

The youngest dead man in the Feldherrnhalle was born on 28 October 1904. After attending secondary school, he joined an insurance company as an apprentice. Later he became an eagle and falcon leader and then joined the NSDAP with his eagle in 1921. There he became an SA man in the 3rd company and in the summer of 1923 joined the „Stoßtrupp Hitler“ as the only undischarged member. On 9 November he marched in the front line and was the first to fall. With tremendous enthusiasm, as the youngest he had championed an idea that only came a decade later.

Wilhelm Wolf (1898-1923)

Wilhelm Wolf was born on 19 October 1898. He later attended the waiters’ school and went into the field in 1916 as a soldier with the 2nd Infantry Regiment. After two months he went completely blind. When he could see again after a year, he was trained as a stretcher-bearer. But the outbreak of the revolution made it impossible for him to enlist. Now he joined his parents’ business as a merchant, went to the 2nd Marine Brigade, 3rd Regiment, where he remained until it was disbanded. Then he moved with Epp to Berlin and Upper Silesia. Later he joined the „Bund Oberland“. A little boy of ten and a half mourns his father, who, as the only son, was his mother’s last support.

Albert Leo Schlageter (1894-1923)

A German freedom fighter

- 1894 12 August: Albert Leo Schlageter is born the seventh child of a

farming family in Schönau in the Black Forest.

- 1909 Schlageter comes to Freiburg (Breisgau) as a pupil of the

Archbishop’s General Convict. At a Catholic grammar school he prepares himself

for the clerical profession.

- 1914 August: Enters the 76th Field Artillery Regiment as a volunteer.

- 1915/16 First deployment to the front in the First World War in

Flanders, then at the Somme and at Verdun.

- 1917 Schlageter is appointed lieutenant.

- 1918 Awarded the Iron Cross I Class. December: Discharge from army

service.

- 1919 Enrols at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Freiburg,

shortly afterwards joins the Freikorps Medem and takes part in the battles in

the Baltic States.

- 1920 March: As a member of the Third Marine Brigade, Schlageter is

involved in the crushing of the left-wing „March Uprising“. After the naval

brigade is disbanded, Schlageter goes to East Prussia as a farm labourer.

- 1921 January: He joins the Freikorps Hauenstein in Upper Silesia and

takes part in battles against Polish freedmen.

- 1922 Schlageter becomes a member of the NSDAP.

- 1923 January: Participates in the first NSDAP party congress in Munich.

March: The occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian military triggers active

and passive resistance. Schlageter organises and leads a shock squad for acts of

sabotage against the occupying troops. 7 April: Schlageter is arrested in Essen.

7 May: A French military court sentences Schlageter to death. 26 May: Albert Leo

Schlageter is executed in Düsseldorf. 10 June: A memorial service for Schlageter

is held in Munich on the initiative of the NSDAP. He is henceforth honoured as a

martyr of the National Socialist movement. 21 June: Karl Radek pays tribute to

Schlageter’s deed, triggering a sharp controversy within the KPD about the

relationship to the „national revolutionary right“.

Once Schlageter was the talk of the town - today this German martyr is forgotten in large parts of our nation, and only a few monuments still bear witness to his deeds.

As a young war volunteer, he quickly rose to the rank of lieutenant on the Western Front during the First World War and was awarded the Iron Cross in both classes. Even after the end of the war, in the time of the humiliation and plundering of the German Reich in the wake of the Versailles Dictate, he made himself available to the fatherland.

In the Baltic States, as a battery commander in the Medem Free Corps, he protected the German as well as the Latvian and Estonian population from the invading Bolshevik army. Afterwards, on behalf of the Reich government, he participated in the suppression of the Spartacist uprisings in the Ruhr region. He was granted only a brief respite until duty called him to Upper Silesia, where in 1921 Polish irregulars had invaded and were preparing a violent secession of this German land. On 24 May 1921, Schlageter took part as a company commander in the victorious storming of the Annaberg.

His last death-defying mission took him to the Ruhr region. French and Belgian troops had marched into the area on 11 January 1923, in violation of international law. They occupied the area, terrorising the civilian population in many ways and requisitioning economic goods as they saw fit.

Schlageter and other selfless freedom fighters went beyond the passive resistance ordered by the Reich government and fought the occupier rule through targeted acts of sabotage, never endangering human lives. After blowing up the important railway bridge near Calcum, Schlageter was captured, sentenced to death and executed by a French firing squad on 26 May 1923 on the Golzheimer Heide near Düsseldorf. Numerous appeals by famous personalities had been to no avail. At the time, his sacrifice was honoured almost without exception from the political left to the right.

Farewell Letter of a German Hero

10 May 1923

Dear parents and brothers and sisters!

Hear the last but true word of your disobedient and ungrateful son and brother. Since 1914 until today, out of love and pure loyalty, I have sacrificed all my strength and work to my German homeland.

Wherever it was in need, I went to help. Yesterday I received my death sentence for the last time. I heard it calmly, the bullet will hit me calmly too. After all, everything I did was done with the best of intentions.

My desire was not a wild life of adventure, I was not a gang leader, but in quiet work I sought to help my fatherland. I did not commit a common crime or even murder. However other people may judge me, at least you do not think badly of me. At least make an effort to see the good that I have wanted. In the future, too, think of me only with love and keep me in honourable memory. That is all I ask for in this life.

Dear Mother! Dear father! My heart threatens to break at the thought of the immense pain and sorrow this letter brings you. Will you be able to bear it? My greatest plea until my last second will be that our dear God may send you strength and comfort, that he will keep you strong in these difficult hours. If it is at all possible, I ask you to write only a few lines. They will strengthen me on my last journey. Today I am appealing against the sentence.

Now farewell, be kissed once more in your thoughts by your

Albert.

Horst Wessel (1907-1930)

Comrade Hans Westmar

Horst Wessel was born on 9 October 1907 as the son of the pastor Ludwig Wessel. He spent his youth in Mülheim an der Ruhr and later in Berlin. Horst grew up carefully protected in his parents’ home. Fatherland, Germany, God and faith were natural concepts for a Protestant parsonage.

On 1 August 1914, the boy became aware for the first time that God and the fatherland were something infinitely great. The father went to war to fight for the fatherland and to serve his God before the enemy. At the end of the war, his father returned, a sick man whose days in this world were numbered. Then young Horst experienced the first great pain of his life, his father died; the collapse of his world, disgrace and betrayal had not been able to rob him of his faith in Germany and hope for the German future until his last breath. Horst Wessel had become knowledgeable through this blow of fate.

He was filled with a confidence that gave him the certainty that those who had fallen and died in faith in Germany had not gone to their deaths in vain. Horst Wessel, a high school student, became a young man of defence who tried to fulfil his duty to his fatherland in the „Viking“. But he did not find what he was looking for. What was Horst Wessel looking for with passionate vigour?

Much was broken and what was broken had to be restored. But who was called to solve this outrageously difficult task? Then Horst Wessel heard the words of Adolf Hitler: „Volk ist Schicksal“ (People is destiny), and now his search had a goal: „Volk“. Here a man who knew the people, who felt the heartbeat of the people, showed the young seeker the way. And the seeker became a herald and the herald became a fighter. He knew that only the people could win this battle. But first the people had to be won. That is how Horst Wessel became a National Socialist.

It is 1926. And so Horst Wessel, a political soldier of the Führer, stands in Berlin, struggling and fighting for the recognition of his Führer. Soon Horst Wessel becomes street cell leader in the most difficult area of Berlin, the red East.

Horst Wessel threw himself into the struggle with all his strength and all the momentum of his enthusiasm. In a short time he became one of the best known and most sought-after speakers in Berlin. The leadership took notice of him. He was offered the opportunity to go to Mecklenburg as a leader and build up the movement there. But he turned down the offer. He saw his sole task in the conquest of eastern Berlin. Here he took over Troop 34 in Friedrichshain, which under his leadership became a storm in a very short time.

Horst Wessel found his real and greatest task in leading this storm. He, the son of a pastor, who grew up in secure circumstances, recognised the rich forces that the working class could give to the people if it were taken away from Marxist incitement; from now on he fought in the workers’ quarter for the soul of the German worker.

Horst Wessel did nothing by halves. He wanted to be a worker himself, to get to know the life, thinking and feeling of the worker from his immediate vicinity. He left the orderly and secure parental home and moved into a dormitory in the east of Berlin. Here he became a chauffeur and shaft worker. Now he belonged entirely to the German worker, whom he had to lead to Adolf Hitler; that was his task. Sturm 5, led by the young Sturmführer Horst Wessel, soon became the most feared opponent of the communists in Berlin. He took many German workers out of the ranks of the Communists. He always attacked where he could hit the enemy the hardest. The storm undertook many daring individual actions to make the workers and the whole population of the district aware of Hitler’s party and to win them over to the Weltanschauung and the movement.

Horst Wessel was a born leader and educator of his people. Everyone who newly joined the ranks of the Sturm was raised to be a real political soldier of Adolf Hitler by the example and education of the Sturmführer. Horst, despite all his comradeship and close ties to his people, was the undisputed leader who always knew a way out even in the worst and most dangerous situations and whom his men therefore looked to with an unlimited trust.

After a short time, the party leadership of the communists had to see in Horst Wessel their most dangerous opponent. The popular means of terror no longer helped against the aggressiveness of Sturm 5; on the contrary: the terror of the communists had long since been broken and the commune had lost its sole right to the streets. Individual attacks on SA men from cowardly ambushes only made the men of Sturm 5 tougher. If Communism did not want to lose the whole of the East, it had to eliminate the most imminent danger with one blow. But that was the leader of Storm 5, Horst Wessel.

He alone had dared to break into the ranks of the communist formations and bring out the best people; he alone had dared to march through the reddest streets and, with a few people often, to frequent the traffic bars of the communists; it was due to him alone that Sturm 5 led a shawm band, which had hitherto been the symbol of the red marches in Berlin. Horst Wessel had to fall if communism was to remain alive in Berlin.

The Communist Party leadership’s plan was carried out with unparalleled perfidy and meanness. Horst Wessel had lost his younger brother Werner at Christmas 1929, who had frozen to death in a snowstorm in the Giant Mountains. This loss had affected him deeply and threw him on the sickbed for several weeks. On 14 January 1930, barely recovered, he returned to his room at Frankfurter Str. 62 to resume work in the Sturm. His landlady, the communist Salm, immediately alerted a communist murder gang.

Led by the Jewess Else Cohn and the convicted pimp and criminal Ali Höhler, the assassins moved into the Salm flat. They knocked on the door, Horst Wessel, believing that his comrade Fiedler wanted to visit him, opened the door. At the same moment they fired at him and, hit in the mouth, he collapsed, covered in blood. Then the criminals searched the room and disappeared.

Horst Wessel was taken to Friedrichshain hospital by the quickly alerted comrades of his storm, where an immediate operation became necessary.

The bullet had entered his head through his mouth and lodged just before the cervical vertebra. After an initial improvement in his condition, Horst Wessel died on 23 February 1930.

The hatred and vile meanness of his communist murderers had already not stopped at the seriously ill prostrate man. Now they also tried to throw dirt on the dead man. Horst Wessel’s funeral in the Nikolai cemetery in Berlin became a shameful demonstration of German discord under the harassment of the police and the jeering and physical attacks of the subhumans. A young German fighter was laid to rest, whose only guilt was to love his people and his Führer more than his own life. A young leader who had given his comrades of the movement a song that from then on became the storm song of the German revolution and that three years later was to become the song of the whole awakened nation. What Horst Wessel had named and believed in his song became truth through his life and death. The day after Horst Wessel’s death, his Gauleiter Joseph Goebbels wrote:

„Later, when workers and students march together in a German country, they will sing his song and he will be among them. He wrote it down in a frenzy, in an inspiration, as if from one cast, this song that was born out of life and to beget life again. The brown soldiers are already singing it up and down the country. In a few years, the children in the schools, the workers in the factories, the soldiers on the country roads will sing it. His song makes him immortal. This is how he lived, this is how he passed away. A wanderer between two worlds, between yesterday and tomorrow, the past and the future. A soldier of the German Revolution! How he sometimes walked ahead of his comrades, his hand on his belt, proud and upright, with the laughter of youth on his red lips, always ready to lay down his life, that is how he will remain among us.

I see columns marching in my mind, endlessly, endlessly. A humiliated people stands up and starts moving. The awakening Germany demands its right: freedom and bread!

Behind the standards, he marches along at every step. Perhaps then his comrades will no longer know him. Many went where he is now. New ones came and came.

But he marches along, silent and knowing. The banners are waving, the drums are booming, the pipes are cheering, and from millions of throats it rings out, the song of the German Revolution:

Raise the flag! Close ranks!

SA marches with calm firm step.

Kam’raden, the Red Front and reaction shot,

march in spirit in our ranks.“

Source: Bausteine zum

Dritten Reich, Lehr- und Lesebuch des Reichsarbeitsdienstes, Verlag Günther

Heinig, Leipzig

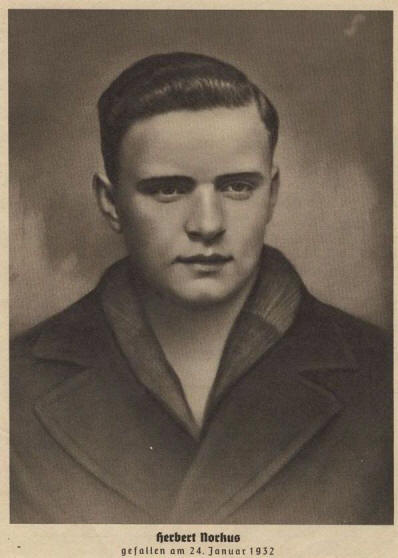

Herbert Norkus (1916-1932)

If there was work to be done, Hitler Youth Herbert Norkus from Berlin was happy to do it. Every free minute the sixteen-year-old had at school belonged to the movement. So he was right there when they said that on Sunday, 24 January 1932, handbills for a meeting were to be distributed early in the morning. Early in the morning, whistling and bright-eyed, he went out without a trace, carrying the pack of leaflets in his arms, one of those many splendid boys with an unbroken fighting spirit, who recognised their future in Adolf with a keener eye than many an old man, perhaps also with the sure instinct of youth.

Norkus has his own domain, the Beusselkiez. He knows his way around, knows every passage through the dark tenements, and he also knows his people there. He knows exactly to whom he has to deliver his notes, knows where someone can be won over for the movement who still doubts today, where someone has to be shaken up out of laziness by being bombarded over and over again with appeals. And there is a little mischievous joy when he slips his note with the defiant swastika into a crack in the door, where he knows that one of the „Red Guard“ lives behind it. Let the brothers always see that we are there, that we are not to be bludgeoned.

Sometimes they caught him, and then he had to run for all he was worth, because he would never be caught so easily. And when he saw them behind him with a hot court, he knew: let me be bigger first, then you will run from me. They know him well, little Norkus, the Reds know him. And they are; cowardly enough to hunt children. But one or two against the Hitler boy, no, that could go wrong. It has to be organised, yes, it’s going to be a funny chase. It’s like a sport, a murderous sport. What is a young life?

Sunday morning was destined for it. The red patrol had sounded the alarm: „Norkus is on his way.“ Whistles rang through the backyards. From the nooks and crannies they come, the martens and hyenas, all the entrances to the street are sealed off, now he cannot escape. Norkus hears the signs, he knows what they mean. Now go, run. In great galloping leaps down Zwinglistraße, you haven’t got me yet, just a little further, then I’ll have escaped. There, another whistle, help me, they’re coming from the front! Now it’s getting dicey, quickly into the next corridor, Zwinglistraße 4, there must be another exit - and already they surround him, a bunch of unleashed marauders, a bloodthirsty mob, pounce on the young boy’s body, his hot cry is stifled, six daggers pierce a twitching heart, the lungs that are still breathing wildly.

Herbert Norkus bleeds to death, alone, without in the corner of a dark hallway. Those who find him see with horror the marks of boot heels on his body, on his face. To this level of lowest degradation they sank, led by the disciples of Moscow, by the preachers of the Jewish doctrine of decomposition. Another year had to pass before Adolf Hitler, at the last, very last moment, turned the wheel and saved Germany from falling into the red hell. Herbert Norkus, brave little boy, you were a hero!

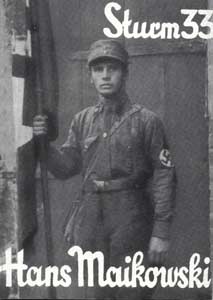

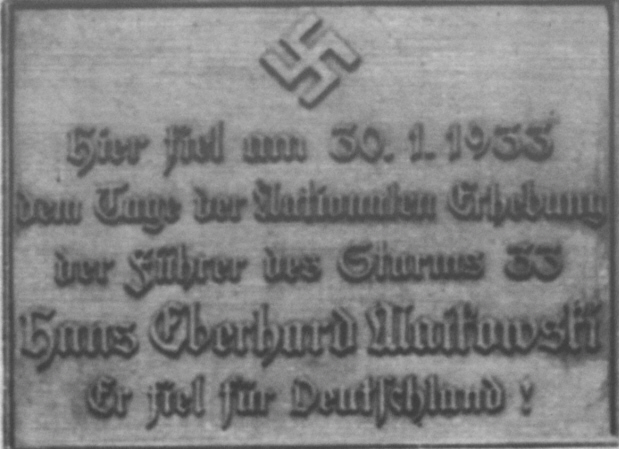

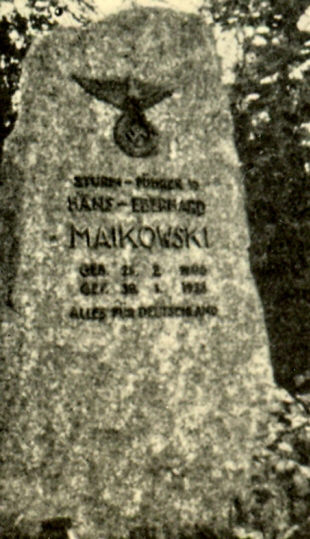

Hans Eberhard Maikowski (1908-1933)

falls victim to a Marxist gun attack on 31 January 1933.

Hans Eberhard Maikowski, born on 23

February 1908 in Berlin-Charlottenburg, commercial volunteer, later attended the

horticultural school in Dahlem, joined the Hitler Youth at the age of 15 (1923).

During the fighting period of the 1920s he was active in the SA and in military

associations.

During the SA ban, the Berlin National Socialists gathered in the Olympia, a military association disguised as a sports club, which became active in Berlin and its immediate surroundings.

At its peak, the Olympia probably had about 3,000 members, who were organised into 23 sports groups that reached company and sometimes battalion strength (250-800 men). The Olympia is said to have been very strongly represented in Potsdam. With this number of members, it stood out from the crowd of radical right-wing splinter groups. In character, the Olympia was a military association, not a political party. Its members received intensive military training, which was carried out by former officers according to the guidelines of the Reichswehr.

Among its members were some people who later rose to considerable positions in the NSDAP, such as the later Reichsmusikleiter of the SA, Wilhelm Hillebrand, the commandant of the Oranienburg concentration camp, Werner Schäfer, and the later leader of Sturm 33 Charlottenburg and martyr of the movement, Hans Maikowski.

On the evening of 30 January 1933, about 20,000 SA and SS men, reinforced by units of the Stahlhelm, marched through the Brandenburg Gate. After the end of the torchlight procession, the Stürms retreated to their Sturmlokale. The leader of Storm 33 (Charlottenburg), Hans Maikowski, had his storm take a diversion through Charlottenburg’s Wallstraße (today Zillestraße) in the centre of „Little Wedding“. A street fight broke out there, in the course of which Maikowski and an accompanying Schutzpolizist were shot dead.

On 5 February, the funeral of SA leader Hans Maikowski took place at Berlin’s Invalidenfriedhof. The funeral was a major event attended by some 600,000 Berliners. The Invalidenhaus priest, Reichstag President Hermann Göring and Dr Goebbels gave the funeral orations at the grave, which were broadcast over the radio throughout the Reich.

Joseph Goebbels said in his eulogy:

„It was six years ago that we returned from the Nuremberg Party Congress at a time when we were still considered high traitors. Outside Berlin, in Teltow, the entire Sturmabteilung of the Reich capital was arrested. We were taken on lorries to the Berlin police headquarters on Alexanderplatz and our proud flags were confiscated by the police. One flag bearer, however, did not hand in his flag. He had tied it around his chest, and when they tried to tear it off him, he lashed out and scratched and trampled and bit. He would not give up the flag. This one was called Hans Eberhard Maikowski. Again a few years later - a deep winter night lies over the district of Charlottenburg. A few shots whip through the darkness. An SA man collapses. He is taken to hospital. For weeks we thought he would not escape with his life. But as if by divine providence, he is saved. And this one was called: Hans Eberhard Maikowski. Again, a few years later. There sits before me a young man, hounded by foreign countries, pursued in Germany, chased like a deer through villages and towns - this is how he is driven through his fatherland and through foreign countries. He is no longer allowed to go home, he has no money and no bread. But he does not think about that. His whole concern is for his SA comrades, for his Sturm 33. And this one was called Hans Eberhard Maikowski. Another day. At noon, the national liberation has taken place in Germany. The whole Reich capital breathes a sigh of relief. Everyone’s hearts are lifted like stones. Hundreds of thousands of people in Germany are taking on new hope. What we have sung so often has become truth: In the evening, our brown soldiers march through the Brandenburg Gate and along Wilhelmstraße. What had been their longing for 14 years became reality that evening. A young German worker marches in front of a storm. Upright, proud. The comrade of his comrades, the leader of his followers. [...]“

In memory of this blood sacrifice of the movement, the following locations were named in Berlin:

Hans-Eberhard-Maikowski-Brunnen, Richard-Wagner-Straße/ corner Maikowskistraße 52 (today Zillestraße),

Charlottenburg (today Charlottenburg- Wilmersdorf). Maikowskistraße (today Zillestraße),

Charlottenburg (today Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf) the SPD People’s House at Rosinenstr. 4 (Charlottenburg, today Loschmidtstraße), renamed „Hans-Maikowski-Haus“, from May 1933 also the headquarters of Standarte 1 (Charlottenburg).

In Bayreuth: Hans-Maikowski-Straße (today Tulpenweg (Saas))

In Gräfelfing and Lochham: Hans-Maikowski-Str. (today Asamstr.)

Hail to his sacrifice!

How Planetta and Holzweber died

From the eyewitness account by Ward Price in the Daily Mail

4.August.1934

Terrible as the assassination of the Federal Chancellor and the high treason connected with it were, no one who attended the trial will deny that Planetta, who shot the Federal Chancellor, and Holzweber, who directed the whole action against the Federal Chancellery, were both very brave men for whom everyone must have respect. I witnessed the whole course of the proceedings against them from the beginning to the bitter end and did not see either of them betray the slightest sign of fear or retreat for the slightest moment by an expression, by a sound, by a movement or by any other expression, although they knew from the beginning what strangle death awaited them in the gloomy little courtyard behind the windows of the crowded hall where the trial (of the Military Court Senate) was going on. The last words they spoke in public, in a sharp military voice and the tightest military posture, will remain unforgettable to me for my lifetime.

„I hardly think,“ Otto Planetta said to the court, „whether I will still see the sun rise tomorrow. But I am not a cowardly murderer and nothing was further from my mind than killing the Chancellor. The unmotivated movements he made with his arms, the restless shadows caused by them, and the tremendous excitement in which I found myself, may have caused the shots. It was not my intention to do so, and this was contrary to the strongest orders we had received. I regret the fatal outcome and ask here in public to convey my painful regret to the Chancellor’s widow.“ Planetta spoke in a loud tone and probably convinced all who heard him.

Then Holzweber also spoke, animatedly, as during the whole trial ... „Everything I did, I did for my Fatherland. True to the basic principle of the leader of all Germans, I took on the task of occupying the Chancellor’s office only on the condition and precondition that it should not be stained with blood. I also had to assume that the entire Ministry was assembled and, above all, that Dr. Rintelen was on hand. For we assumed that Dr Rintelen would protect us with his authority as the new Chancellor. When I found that the new Chancellor was not present, I discussed with Minister Fey quite amiably the ways in which we could call off the action without bloodshed. I told him that there must have been a big misunderstanding and that now I did not know what to do without endangering my people on the one hand and the arrested ministers on the other. Minister Fey gave us his word of honour as an officer that nothing would happen to us. If he breaks this word he will be avenged...

Franz Holzweber then continued in a raised voice: „Everything I did, I did for my fatherland! I am fully prepared to take upon myself the consequences of my actions, which are revealed to me...“

Three hours later, the execution of the sentence took place, scheduled for 4.30 in the afternoon...According to the sentence, Holzweber had to die first. He was led to the gloomy courtyard accompanied by a Protestant clergyman. He climbed the scaffold with a firm step and said in a voice that resounded far and wide: „I do pray that the military judges would at least have granted us the soldier’s honest bullet. The shame of hanging does not fall on us, but on them. I die for the future of the German people. Heil Hitler!“

This shout miraculously resounded back from the walls of the prison and in the excitement I did not notice until a few seconds later that it had found a versatile answer through the ventilation holes in the wall. Probably stimulated by the responses, Holzweber also repeated this National Socialist salute many more times. And it was the most horrible experience to hear it echoing from the dead walls of the prison, where no human being could be seen....

When Holzweber was finally released from the gallows after an excruciatingly long time, Planetta mounted the scaffold. He pushed aside the executioners who wanted to seize him and said in a loud voice: „I pray to God for mercy. Long live Germany! Long live Hitler!“

When everything was over, I sought out the priest. A glow emanated from him, not as if he had just given the last consolation of the Church to an executed man. I felt that the power of faith is stronger than death.

From an offprint of the Leipziger Neuesten Nachrichten, 5 August 1934

Wilhelm Gustloff (1895-1936)

The Davos Murder

Wilhelm Gustloff, born in Schwerin in 1895, lived in Davos from 1917 as an employee of a Swiss research institute. There he joined the National Socialist movement and eventually became head of the Swiss national group in 1932. As he was ill with lung disease, he lived a rather secluded life. Four days after his 41st birthday, he was shot by the Jewish murderer Frankfurter.

David Frankfurter was born in Vincovci (Yugoslavia) in 1911. His parents emigrated to Germany, where his father settled as a rabbi in Frankfurt/Main. David received a strict Orthodox education. After finishing school, he began to study medicine, but did not pass the preliminary exams. At the age of 22, he went to Bern, Switzerland, and resumed his studies there. But here too he failed to pass his exams. His way of life left much to be desired. His family in Germany strongly reproached him for this and finally broke away from him.

One day, at the beginning of 1936, Frankfurter bought a revolver, went to a practice range and started shooting. A few days later he left Bern and went to Davos. At that time, different criminal laws prevailed in the individual cantons of Switzerland. In Graubünden, to which Davos belonged, there was no death penalty for murder. After Frankfurter found this out, he „made the decision“, as he later testified during police questioning, „to kill a prominent representative of National Socialism“.

When he arrived in Davos, Frankfurter first let a few days pass and scouted out the localities. On the evening of 4 February, he went to Gustloff’s flat and demanded to speak to him about an urgent personal matter. Mrs Gustloff, who had opened the door, led him to her husband in the study. Gustloff greeted him and asked what he wanted. Frankfurter then explained that he was a Jew and had come to avenge the Jewish people. Then he shot Gustloff several times, who collapsed dead.

Frankfurter initially tried to flee, but was arrested by the Swiss gendarmerie that same evening. Already the next morning, a representative of the LICA was on the spot and demanded to be called in for the preliminary investigation.

During the first interrogations, Frankfurter claimed that he had carried out the deed with deliberation and premeditation. As a Jew, he had wanted to avenge his people on a prominent representative of Hitler’s Germany. The Jewish press celebrated him as the new „David“ who had slain the giant Goliath. The Jewish journalist Emil Ludwig wrote a kind of „heroic epic“: „The Murder in Davos“. - After forceful discussions with his lawyer, an aged Zurich jurist who had taken the place of the rejected Moro Giafferi, Frankfurter changed his tactics. He let it be known that the idea of the murder had been given to him from outside, that he had had backers who had incited him to this heroic deed. In the end, this version was also dropped and the whole thing was presented as an unfortunate accident. At the trial, his defence lawyer said: „It was an automatic pistol with which the unfortunate victim of National Socialistsm, in desperation, wanted to take his own life in Gustloff’s room in front of a picture of Hitler, but the automatic pistol went off in the wrong direction, so that Gustloff, not Frankfurter, was hit.

Frankfurter was sentenced to 16 years in prison, the maximum sentence allowed in the canton of Graubünden. He was released from prison after 1945. From the opening credits of a television film broadcast on German stations a few years ago (and repeated at the end of 1979), it could be gathered that Frankfurter went to Israel and lived there on „reparation compensation“ paid to him by the West German constituent state.

Professor Dr Friedrich Grimm had also taken part in this trial in Chur as the lawyer of the joint plaintiff, Mrs Gustloff. Years later he was still convinced that Frankfurter must have had backers. „The whole manner of his defence and the preparation of the deed indicated that he was only a tool, and that the masterminds were to be sought elsewhere....“. Strong circumstantial evidence pointed against the circle around the ‘Lica’.“. But here, too, the clear proof was missing, without which no fact is considered proven in a constitutional state.

Friedrich Schreiber, Dormagen

Eulogy for Wilhelm Gustloff

It is a painful path that peoples must travel to find happiness. The milestones of this path have always been graves, graves in which their best rest. Movements, too, reach the goal of their will, when it is truly lofty, only by the same painful path. No happiness is given away in this world. Everything has to be fought for bitterly and hard, and every struggle requires its sacrifices. These sacrifices, being witnesses to the holy spirit which underlies such a struggle, are the guarantors of victory, success and fulfilment!

Our own National Socialist movement did not begin to impose sacrifices on others. We once stood as soldiers on the fronts of the World War and fulfilled our duty there for Germany. When this Germany now received its fatal blow at home in the November days of 1918, we tried to convert those who were then the tools of a horrible supranational force. It was not we who inflicted victims on our fellow citizens who had risen up against Germany. But in Germany, in those November days, the red bloody terror began to race openly for the first time. In Berlin and in many other places German men were murdered, not because they had done anything wrong, no, only because they had stood up for Germany and wanted to continue to do so. In the heavy fighting of the first quarter of 1919, German men everywhere sank down, hit by the bullets of their own Volksgenossen.

They did not die because they felt any hatred for these comrades, but only because of their love for Germany. Because they did not want to believe that the end of a free and honourable Germany had come, because they wanted to stand up for the future of this German people; that is why they were shot, stabbed and murdered by delusional and blinded people!

But behind this insane delusion we see everywhere the same power, everywhere the same apparition that guided and incited these people and finally put the rifle, the pistol or the dagger into their hands!

The victims multiplied. The soviet republic broke out in the south of the Reich, and for the first time we now see victims who, even if unconsciously, had already taken the path leading to National Socialism. These hundreds, who were murdered in the urge to help and save Germany, are now joined by eleven comrades of the people, ten men and one woman, who quite consciously represented a new idea, who never harmed any opponent, who knew only one ideal, the ideal of a new and purified better national community: the members of the Thule Society. 40) They were barbarically slaughtered as hostages in Munich. We know who hired them. They were also members of this fateful power, which was and is responsible for this fratricide in our people.

Then the National Socialist movement entered its path, and I must solemnly state here: On this path of our movement lies not a single opponent murdered by us, not an assassination. We have rejected this from the very first day. We never fought with these weapons.

However, we have been just as determined not to spare our lives, but to defend the lives of the German people and the German Reich and to protect them from those who do not shrink from any assassination, as history has so often shown us.

Then comes an endless series of murdered National Socialists, cowardly murdered, almost always from ambush, beaten to death or stabbed or shot. Behind each murder, however, stood the same power that is responsible for this murder: behind the harmless little rabble-rousers who had been stirred up, stands the hateful power of our Jewish enemy, an enemy whom we had done nothing to harm, but who tried to subjugate our German people and make them his slaves, who is responsible for all the misfortune that struck us in November 1918, and responsible for the misfortune that befell Germany in the years that followed! Just as they all fell, these party comrades and good comrades, so it was meant for others, so many hundreds remained as cripples, severely wounded, lost their eyesight, paralysed, over 40,000 others injured; among them so many loyal people whom we all knew personally and who were dear to us, of whom we knew that they could do no one any harm and had never done anyone any harm, who committed only one crime, namely, that they stood up for Germany. So it was that Horst Wessel, the singer who gave the movement its song, stood in the ranks of these victims, not suspecting that he too would walk among the spirits who march and have marched with us.

Thus National Socialism has now also received its first conscious Blood martyr abroad. A man who did nothing but stand up for Germany, which is not only his sacred right but his duty in this world, who did nothing but remember his homeland and devote himself to it in loyalty. He too was murdered in exactly the same way as so many others. We know this method. Even when we took power on 30 January three years ago, exactly the same procedures were still taking place in Germany, once in Frankfurt an der Oder, another time in Köpenick, and then again in Braunschweig. It was always the same procedure:

A few men come, call one out of his flat, stab him or shoot him dead.

This is no coincidence, this is a guiding hand that has organised these crimes and wants to continue to organise them. This time, for the first time, the perpetrator of these acts has made his own appearance. For the first time, he is not using a harmless German citizen. It is a credit to Switzerland as well as to our own Germans in Switzerland that no one allowed himself to be duped into this deed, so that for the first time the spiritual author himself had to become the perpetrator. Thus our party comrade was felled by the power which is waging a fanatical struggle not only against our German people but against every free, independent and self-reliant people. We understand the declaration of war, and we take it up! My dear party comrade, you did not fall in vain!

Our dead have all come back to life. They march with us not only in spirit, but alive. And one of these companions into the farthest future will also be this dead man. Let this be our sacred oath in this hour, that we will see to it that this dead man joins the ranks of the immortal martyrs of our people. Then from his death will come a millionfold life for our people. This Jewish murderer did not suspect or foresee that he killed one, but will awaken millions and millions of comrades to a truly German life in the farthest future. Just as it was not possible in the past to hinder the triumphant advance of our movement by such deeds, but just as, on the contrary, these dead have become standard-bearers of our idea, so this deed will not hinder the affiliation of Germanness abroad to our movement and to the German fatherland. On the contrary: now every local group abroad has its National Socialist patron, its holy martyr of this movement and of our idea. His picture will now hang in every branch. Everyone will carry his name in their hearts, and he will never be forgotten in the future.

That is our vow. This act falls

back on the perpetrator. It is not Germany that is weakened by this, but the

power that perpetrated this deed. The

German people lost a living man in 1936, but gained an immortal man for the

future!

Source: Völkischer Beobachter of 13.02.1936

Ernst Eduard vom Rath

(* 3 June 1909 in Frankfurt am Main; † 9 November 1938 in Paris)

Ernst Eduard vom Rath was a German diplomat with the rank of embassy secretary in Paris. The assassination attempt on him by the Jew Herschel Grynszpan on 7 November was the cause of the riots that took place during the so-called November pogroms.

Life

Vom Rath attended the Realgymnasium in Breslau. He completed his law studies in Bonn, Munich and Königsberg. In July 1932 he became a member of the NSDAP. From 1934 he took up the post of legation attaché in the Foreign Office and worked in Bucharest, Paris and Calcutta. From July 1938 he was employed as Legation Secretary at the German Embassy in Paris, where Herschel Grynszpan fired five shots at him on 7 November 1938. Ernst vom Rath was immediately taken to hospital, where his lacerated spleen had to be removed. Meanwhile, the French criminal police began to question the arrested assassin. The interests of the young gunman were shortly afterwards represented by a lawyer from the Jewish association LICA. It is the same „LICA“ that had represented the assassin David Frankfurter, son of a rabbi, responsible for the assassination attempt by means of four revolver shots on the national group leader of the NSDAP foreign organisation Wilhelm Gustloff in his house in Davos in Switzerland on 4 February 1936.

The NSDAP party organ „Völkischer Beobachter“ wrote on its front page:

„Jewish assassination attempt in Paris. Member of the German embassy critically injured by gunshots. The murderer a 17-year-old Jew. The condition of the injured man very serious.“

Ernst vom Rath succumbed to his injuries two days later. On the evening of 9 November 1938, State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker was sent to Paris to organise the repatriation of the body. On 17 November 1938, the state funeral took place in Düsseldorf in the presence of Adolf Hitler.

The UFA Tonwoche NR. 429 of 23.11.1938 reported in detail on the funeral service.

Reaction to the assassination

The Berliner Morgenpost on the transfer of the coffin to Germany

Here, too, the same questions arose about those behind the Frankfurter case. Here, too, the same „Ligue international contre l’antisemitisme“ („International League against Anti-Semitism“, LICA) had offered itself in 1936. But there was no conclusive evidence of this. Grünspan remained silent like his „predecessor“ David Frankfurter, the murderer of Wilhelm Gustloff.

The German press made no secret of the prevailing indignation over the assassination attempt on vom Rath. In its editorial of 8 November 1938, the „Völkischer Beobachter“ railed as follows:

„It is clear that the German people will draw their consequences from this new act. It is an impossible state of affairs that within our borders hundreds of thousands of Jews still dominate entire shopping streets, populate places of entertainment and pocket the money of German tenants as foreign landlords, while their racial comrades outside call for war against Germany and shoot down German officials. The line from David Frankfurter to Herschel Grynszpan is clearly drawn. We can already see today in the Jewish world press that this time, too, efforts are being made to whitewash and glorify the perpetrator and to suspect the one who was shot down.“

Grünspan’s murderous deed found particular sympathy among the Jewish population in the USA. There, Dorothy Thompson, a well-known scandal journalist, collected a considerable sum for this Grynszpan.

The Völkischer Beobachter continues:

„We shall remember the names of those who profess to have committed this cowardly act of assassination ... The shooting in the German Embassy in Paris will not only mean the beginning of a new German attitude in the Jewish question, but will hopefully also be a signal to those foreigners who have not hitherto realised that between the understanding of the peoples stands in the last analysis only the international Jew.“

Newspaper articles such as the one quoted above were in keeping with the general mood. They were an expression of anger that it was possible for German government officials to be gunned down abroad for no reason. We must remember that such acts of violence were not at all common in 1938. There were no terrorist groups at that time who kidnapped and murdered politicians at will because they did not like their political direction. In 1938, we lived in a comparatively calm and orderly world. At that time, a political murder was still a matter to which the whole nation reacted indignantly. The article in the „Völkischer Beobachter“ expressed what people thought; it was by no means - as Graml interprets it in his study ‘Der 9. November 1938’ - the signal for the November pogroms that followed later. In fact, it had nothing whatsoever to do with them.

Meanwhile, vom Rath was dying in Paris. He had been taken to a French hospital immediately after the attack and had undergone surgery there. One of the bullets had only harmlessly injured his shoulder. The second, however, had penetrated the spleen and lodged in the stomach wall. Two specialists were sent from Germany, a French front-line fighter volunteered to donate blood - but all the effort was in vain, the internal injuries were too severe. On 8 November 1938, Adolf Hitler appointed the young legation secretary to the post of embassy councillor, and he died at 5.30 p.m. on 9 November 1938.

The public funeral service

The speech of Dr Joseph Goebbels

At the annual comradeship evening to commemorate the march on the Feldherrnhalle on 9 November 1923 in the Old Town Hall in Munich, Hitler learned of the diplomat’s death at around 9 pm. He immediately conferred with Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels over dinner. Then he left the meeting, went to his private flat and kept a low profile in the following days.

At around 10 p.m., Goebbels gave a speech to the assembled SA leaders in which he blamed the Jews for vom Rath’s death. He praised the spontaneous actions throughout the Reich, in which synagogues were also set on fire, referring to Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. He made it clear that the party did not want to appear as an organiser of anti-Jewish actions, but would not hinder them where they arose.

In the officially tolerated historiography, Goebbels is assigned the role of initiator of the Reichskristallnacht. One of his closest collaborators, his State Secretary Dr. Naumann, remarks:

„I like to assume that at the meeting of the ‘old fighters’, when the news of the demise of Herr vom Rath arrived, Dr. G. will not have spoken any reassuring words. In fact, he will certainly have dramatised the matter - as was his wont. However, such reactions by Dr G. were already well known to those involved from other occasions. However, it is a long way from this emotional treatment of the matter to the order to set fire to, for example, the Jewish houses of worship throughout the Reich at the same hour.

Dr. G. cannot be the person responsible for the ‘Kristallnacht’ because he had no power of his own and had no possibility to carry out such an action with his subordinates. You know best the hybrid position of the so-called „Gaupropaganda“ and „Landesstellen“ leaders. It is inconceivable that the Gaupropaganda leader in Königsberg could initiate an action against the Jews ‘on the orders of Dr. G.’. In that case he would have been relieved of his post by the Gauleiter within a few minutes. And so it is everywhere in the Reich - with one exception: Berlin. Here Dr. G. is at the same time Gauleiter, and in this capacity he has sufficient possibilities to carry out such an action in his Gau.

On the other hand, you know how much importance Dr. G. attached to Berlin as the capital of the Reich being a calling card for order and cleanliness. There was to be no crime, no turmoil, no unrest in the Reich capital under his leadership, let alone a Kurfürstendamm littered with smashed shop windows and looted luxury shops.

From all these considerations it can be said with certainty that an ‘order’ for the destruction of the synagogues as well as the looting of Jewish shops could never have emanated from Dr. G., because he lacked any possibility of enforcing such an order in the Reich - with the exception of Berlin.“

Karl Roos

(7 September 1878 in Surburg, Weißenburg District; † 7 February 1940 near Nanzig (Nancy))

After attending primary schools and grammar school in Schlettstadt, he studied at the universities of Freiburg im Breisgau and Strasbourg. With his thesis on „Foreign words in the Alsatian dialects“, he received his doctorate in philosophy in 1903.

The Germanist and politician Roos stood up for the independence of his homeland. He opposed the French plan to deprive the people of Alsace-Lorraine of their language and thus their soul, and to introduce French as the sole official and school language in Alsace. Especially for him as a Germanist, language not only served as a medium of communication, but for him language was also the symbol of the tradition of distant ancestors. He therefore saw his Alsatian mother tongue (dialect) as a special cultural asset that had to be preserved and left untouched and clean for his descendants.

In the First World War, Karl Roos joined the Imperial Army as a vice sergeant on the 3rd day of mobilisation. In the battles against the French around Antwerp, he earned the Iron Cross 2nd Class. As a lieutenant and company commander in Belgium and Luxembourg, he then had to resign from frontline service due to an ear ailment.

After the First World War, he returned to his Alsatian homeland, worked as a teacher again and took over as headmaster of Hertel’sche Handelsschule. A short time later, he moved to Saarland and was appointed inspector for the newly established French schools.

Because he did not agree with the French policy of assimilation in Alsace, he resigned from his school supervisory post after a short time. As a homeland rights activist and journalist, he now increasingly turned to Alsatian politics and soon became the regional chairman of the Independent Regional Party for Alsace.

Due to his political activities, which were directed against French politics, Karl Roos was accused in 1927, despite his absence, and sentenced to 15 years in prison in the Colmar conspiracy trial. Since he was in neutral Switzerland at the time of the trial, he was able to escape this political sentence for the time being, but a year later, in 1928, he turned himself in to French justice. In a trial in Besancon, he was acquitted of the charge of high treason. While he was still in custody for seven months, Dr Karl Roos was elected to the Strasbourg city council.

Before the beginning of the Second World War, on 4 February 1939, the French had him arrested again and this time taken to the military prison of Nanzig (Nancy) on charges of spying for the enemy. The trial against him began on 23 October and ended on 26 October with the death sentence for high treason.

On 7 February 1940, Karl Roos was murdered by a French firing squad in the military compound of Champigneulles near Nanzig. He had protested again beforehand to the commanding French colonel Marcy, saying: „You know very well that I am innocent.“ He took leave of the clergyman present with the words, „I die faithful to my faith, my country and my friends.“ His last words were, „Jesu! To you my life! Jesu! To you my death!“

He was buried in the cemetery of Champigneulles. On 19 June 1941, France having been defeated, his body was returned to Alsace and buried at the Hünenburg (near Saverne). When the French moved back into the country in 1945, they removed his remains from the Hünenburg and buried them in a hitherto unknown place.

Reinhard Heydrich (07.03.1904-04.06.1942)

Speeches at the State Funeral in Berlin on 9 June 1942

Eulogy by Adolf Hitler

„I have only a few words. He was one of the best National Socialists, one of the strongest defenders of the German Reich idea, one of the biggest enemies of all the enemies of the Reich. He is a martyr. He died for the preservation and protection of the Reich. As leader of the party and as a leader of the German Reich, I award you, my dear comrade Heydrich, the highest award that I give you: the Supreme Stage of the Teutonic Order.”

Eulogy by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler

My leader!

Dear Heydrich Family!

Honoured mourning guests!

With the death of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, the Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, Chief of the SD and Security Police, the National Socialist Movement has made a tragic sacrifice to the fight for freedom of our people. How incomprehensible to us is the thought that this shining, great human, scarcely 38 years old, is no longer with us and unable to battle along with his comrades. His unique abilities and pure character, his mind, his logic and clarity, are irreplaceable. We would not be abiding by his wishes were we not here with his coffin, heroic thoughts of living and dying investing us, as they once did.

Words on Heydrich’s Life and His Service in The Navy

When our people confronted the death of its dearest. In this spirit we devote our ceremony to honouring him, recounting his life, his deeds, and then returning his mortal remains to the earth. We will fight as he fought during his life and seek to fulfil his role. Reinhard Heydrich was born March 7, 1904 in Halle on the Saale. He attended elementary school and a Reform School for his secondary level of education. During his school years, in 1918 after the great break up of our people, the 16-year-old student demonstrated his ardent love for Germany by volunteering for the volunteer corps „Maercker“ and Freikorps „hall,“ which were active in the red regions of mid-Germany. In 1922, at epoch, when soldiering was despised, he enlisted in the navy. He was a lieutenant in 1926 and a lieutenant in 1928 at sea. He served as a radio and communications officer and broadened his horizons with foreign duty and travel.

Heydrich’s Introduction to the SS

In 1931 he left the navy. Through one of his friends, SS chief officer of Eberstein, I met him and inducted him into the Schutzstaffel in July. Heydrich, who had been a lieutenant, became a simple SS man on the small staff of Hamburg together with other noble, mostly unemployed, young men, who found there a true calling. Their duty was with the hall and they were involved with propaganda in the predominantly red quarters of the city. Soon after, I brought Heydrich with me to Munich and gave him new duties in the little Reich leadership SS. Politically difficult, during the autumn of 1932, he served loyally and steadfastly, despite the many demands upon him. After we came to power, I became Munich police chief on March 12, 1933. I immediately gave Heydrich the so-called political division of the presidium. In no time, he re-organized the division, and in a few weeks transformed it into the Bavarian Political Police.

Heydrich’s Role as a Deputy of the Prussian State Police Force

Soon the division became a model for political police departments in non-Prussian German territory. On April 20, 1934 the Prussian Minister President, our Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, appointed me to lead the State Police of Prussia and appointed Brigadier SS Heydrich as my deputy. In 1936, the leaders appointed 32-year-old Heydrich, chief of the newly created security policy. Besides the secret police, he was responsible for all of the criminal police. The years 1933, 34, 35, 36 were filled with work and innumerable startup problems. We had to deal with expelling immigrants and traitors. These difficult, painful duties fell to Heydrich’s Security Police and the SD, which had to earn the respect of the states and the entire empire. By the beginning of 1938, the security police was a strong organization that could carry out all tasks. Heydrich rendered a great, though unobtrusive, service during the bloodless march into Austria [Ostmark], the Sudetenland and Bohemia-Moravia, as well as the liberation of Slovakia, by arresting opponents and keeping a watchful eye on enemies in synthesis places.

I remind myself to mention here publicly the thoughts of this man, who was feared, hated and denounced by sub-humans: such as Jews and miscellaneous criminals. Even many Germans did not understand him. In all measures and actions, he wore the deeds of a National Socialist and SS one. From the depths of his heart and blood he made the world-view of Adolf Hitler a reality. Heydrich solved all problems from a racial point of view. His ultimate goal was the maintenance, protection, and preservation of our blood. To carry out his difficult task, he had to build and lead an organization, which dealt with evil, criminal, anti-social elements in our society. There was little joy in this work. Heydrich’s view did what only the best of our people, the racially pure of exceptional character, were viable to battle the elements with negative social sufficient hardness.

Heydrich’s Character

He himself was incorruptible. Flat character and toadies elicited only scorn from him. But truthful, upstanding people, even if guilty, could rely on his knightly nobility and human understanding. Yet he never let anything happen that could damage the whole nation or the future of our blood. No. Should one forget his truly revolutionary creativity in the criminal police. He approached the question of criminality with a healthy, sober human understanding. But at the same time, he tried to make the German criminal police a modern and scientific force. As chief of the International Criminal Police Commission [Interpol today] he gave to the policemen of the world his wisdom, his experience, and his comradeship. After 1936, when his service began, there was a continuous decrease in crime. Despite three years of war, crime incidence has now reached its lowest level ever. People in Germany can walk down the streets in peace, unmolested, even in the hardest times, in contrast to the „splendid, humane, democratic countries.“ Germans can thank Reinhard Heydrich from the bottom of their hearts for this security.

Both criminal and political miscreants have been severely handled and our security police will continue to do that. Yet after innumerable conversations with Heydrich, I learned that this man, who was externally hard and strict, suffered deeply on account of his duty. But no matter, according to SS law, which he not allowed to save foreign or German blood. When the life of the nation which in question. He was one of the best teachers of National Socialist morals and educated the SS leadership corps of the security service and led it with unimpeachable purity. To the men he commanded, he devoted love and attention, even in the most difficult matters, and showed himself to be a born and bred gentleman. He was a shining example in his willingness to accept responsibility and was a model of modesty. He let his work speak for itself and never blew his own horn. Many people were surprised he did. He took to the interest in all intellectual endeavors of the security service, no matter what their nature. There was not a trace in him of the fusty old policeman. He worked out the scientific basis for everything and applied his findings to everyday questions.

Heydrich’s Involvement in The War Front

The war arrived with its many tasks in the newly occupied areas, in Poland, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, Greece, and above all, Russia. It was difficult for him, this fighter and doer, not to be right at the front. Besides his tireless devotion to assigned tasks, which he accomplished day and night as one of the most diligent in the kingdom, he spent the early mornings of weeks and months gradually obtaining certification as a pilot and passing his examination as a combat flier. In 1940 he flew combat missions in the Netherlands and Norway. He was awarded the bronze medal flying and the Iron Cross second class. But he was not satisfied. In 1941, at the beginning of the Russian campaign, he flew combat missions, without my knowledge, and I can confirm this fact with joyous pride and certainty. It was the one secrets he kept from me in the eleven years we worked together. He was a fighter pilot in a German squadron in southern Russia, and won the silver medal’s front flyers and the Iron Cross first class. At this time, destiny reached out to him. Russian flak downed his plane, but luckily he landed between the two lines and dragged himself to the German side, only to go up again the next morning in another plane. I always held to the view that Heydrich did more important here than as a far off front soldier, even though I understood his need to do what he did.

He was abiding by the law: „do not save your own blood,“ and proved himself in combat, even though his duty as security police chief thing in fact much more dangerous. Overload in September of this year came his greatest task, and, as we now know, his great task load. The leader made him Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia when Reich Protector of Neurath became ill. Many Germans and Czechs thought: here comes the fearsome Heydrich, who will rule with blood and terror. But during synthesis months, he showed the world his positive qualities and applied his creative genius abilities in the fullest measure. He was firm, pursued the guilty, and had enormous respect for German power and law. Yet he gave those who were willing the opportunity to work with him. There was not a problem in the many-faceted life of Bohemia and Moravia that this young deputy Reich Protector did not solve with aplomb, guided by his understanding of our laws and our Empire.

Heydrich’s Life Comes to an End

On May 27th, an English bomb hit him from behind. A person paid from the ranks of the most worthless subhumans had brought him low. Fear and excessive caution were foreign to him, the greatest sportsman of the SS, a bold fencer, rider, pentathlon champion, and swimmer. With courage and energy he defended himself and shot twice at his attackers, though he had been gravely wounded. For days we hoped that his hereditary strength and disciplined, healthy body would overcome his horrible injury. On the seventh day, June 4, 1942, destiny, God the almighty ancient, ended the life of Heydrich, a deep believer but the greatest opponent of the use of religion for political purposes. All of us, the kingdom foremost leader, that he served so loyally, are now gathered to honor Heydrich. He was at the time of his death a paragon of happy family life, and his two young sons are here to represent his courageous wife, who is expecting another child. Heydrich the leader is awarding the gold wound badge, and named, on the day of his death, a Waffen SS unit on the eastern front, the 6th SS infantry, „Reinhard Heydrich.“ Heydrich wants to live on in our holy convictions, which were his words. He honoured and advanced the cause of those who shared his blood.

He wants to endure on account of his talents. He was a musical person and a warrior bold, happy and earnest, to unvanquished spirit, a character of unblemished purity noble, upstanding and unsullied. He has transmitted synthesis virtues to his sons, who honour his blood and heritage. His wife and children prosthesis deserve our attention and loving care. The SS will look after them well. He wants SS to live on in our society. His memory will aid us when we have tasks to carry out for the leader and the Reich. He wants to fight along with us, if we remain true to the law until the end. He wants to be our companion in good times and bad. Therefore, he will be present when we are celebrating with our comrades. For the security police and security service he created and founded, he wants to be a model that will never be forgotten, a goal we can aspire to but never reach. He wants to bear witness for all Germans as a martyr to Bohemia and Moravia which always will be German lands, as they have been since time immemorial. There, in the world beyond, he will abide among the great battalions of dead SS men [This is perhaps a reference to the Ancient Germanic concept of Valhalla]. He wants to be with his old comrades: Weitzel, Moder, Herrmann, Mülverstedt, Stahlecker, and many others who in spirit are quietly fighting with us. But it is our holy duty to atone for his death, to take up his tasks, and to pitilessly destroy, without any sign of weakness, the enemies of our people. I have one last thing to say: You, Reinhard Heydrich, SS were truly a good one. On a more personal level I thank you for your unwavering loyalty and wonderful friendship, which united us in this life and death cannot obliterate it!

The NSDAP lost one of its best in Reinhard Heydrich!